Perhaps the biggest weight off my shoulder is my critical analysis. I’ll admit I am not completely proud of it. I feel like I could have added more pages to it, and maybe made my question towards my fellow classmates a bit broader. But I think it was strong enough, and I’m glad I get to focus more on my creative work.

Excerpt:

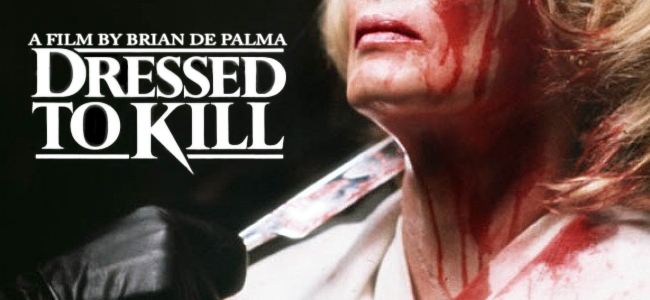

Dressed to Kill

Kate Miller, played by Angie Dickinson, is a frustrated housewife in New York City. Her husband ignores her, her son is more invested in his inventions than anything else, and she has no excitement in her life. It gets to the point where she finds herself flirting with her therapist Dr. Robert Elliott, played by Michael Caine. It isn’t until she visits the Met and sees a handsome stranger that she finally finds excitement in her sex life.

Alas, such excitement is cut short as that evening sees Kate Miller stabbed to death with a razor by a mysterious woman. Robert Elliot soon discovers it is a patient of his named Bobbi, a transgender patient who Elliott refused to sign the sex reassignment surgery papers for. This tragic event sees Robert Elliott, Kate Miller’s son Peter, played by Keith Gordon, and the sole witness, a prostitute named Liz Blake, played by Nancy Allen.

This noir thriller and slasher was directed by Brian De Palma, who himself was born in Newark, New Jersey and grew up in Philadelphia. De Palma first enrolled as a physics major at Columbia University, but found himself invested in film after viewings of both Citizen Kane and Vertigo. And so, after earning his undergraduate degree, he later enrolled as a theater major at Sarah Lawrence College, where he fine-tuned his craft and started developing his first few features. Several of these features, like The Wedding Party, Greetings, and Hi, Mom! also featured a then-unknown Robert De Niro.

De Palma would continue to work on small, independent features, but got his big break with the 1976 movie Carrie, based on the 1974 Stephen King novel. In development before the King book was even on the bestseller list, Carrie was a box office hit, earning $33.8 million domestically, and boosting the careers of Sissy Spacek and John Travolta.

The financial success of Carrie allowed De Palma to work on more personal projects through the 1980s, one of them being Dressed to Kill. De Palma developed Kill as a personal project, mainly to tribute one of his cinematic heroes Alfred Hitchcock. De Palma has many unique elements that make his films enthralling, especially in his camera shots. Split-screen techniques showcasing two events happening at once, split focus shots that allow a foreground and background object to both be in focus, slow motion to allow more suspense. But as a filmmaker, De Palma loves to pay homage to films and filmmakers that shaped his artistry. Hitchcock is no exception.

In the case of Dressed to Kill, much of the film’s plot directly parallels Psycho. Like Psycho, the lead actress is stabbed in the first death. Like Psycho, there’s a shower scene that plays a significant role in the story (though both scenes have different functions). Like Psycho, the killer is…a man dressed as a woman, with a psychiatrist explaining their backstory. Sadly, the way this reveal is handled in Dressed to Kill is far more toxic and uncomfortable, though that will be discussed later.

The only real difference between the two is Kill is much more violent and bloody, another staple of De Palma’s work. His films were heavily violent, often resulting in these films garnering controversy with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). This film even garnered an “X” rating, which forced De Palma to cut about 30 seconds of the film in order to get an R.

However, perhaps the biggest homage to Hitchcock is a sense of voyeurism, or the idea of peering and spying on other people’s activities without them knowing. Much of this is found during the actual mystery, as the son Peter and witness Kate try to bring justice to Kate Miller’s death. But the finest example is when Kate visits the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the film is set in New York and the majority of the film was shot in New York, this sequence was actually filmed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I feel as if this was a deliberate, genius move on De Palma’s part, letting the most fantastical and layered sequence of the film take place in his own childhood playground.

The scene opens with Kate looking around the museum by herself. Large paintings surround her. A couple placing their arms on each other’s backs are enjoying the view. A single man tries to start up a conversation with a single woman. A little girl is impatiently begging her mother to move along so she can explore the museum. She finds herself on an island. She may have a family, but she doesn’t have something that truly makes her happy like the people around her.

Suddenly, a man sits down next to her. The score by Pino Donaggio starts. After a few seconds, they both look at one another, Kate with a smile, the man with a blank expression. Kate soon takes off her glove, showing her wedding ring. The man gets up and leaves, with Kate feeling as if that removal cost her a chance with the handsome gentleman who could turn her life around. She soon stands up, leaving her glove on the ground, and follows the man throughout the museum. There’s twists and turns throughout this Philadelphia establishment’s corridors as they continue walking. Kate thinks she lost him, only for him to appear behind her back.

As Kate starts to walk away, pretending as if she doesn’t care about him, the man starts to watch and follow her. And after both figures move to different parts of the museum, De Palma has a close-up on Kate’s face, distraught she lost the man that could turn her life around. But lo and behold, the man saw her glove on the ground, puts it on his hand, and touches Kate’s shoulder, as they finally have their first true interaction. Kate rejects him, out of fear she will lose the sanctity of her marriage.

And then, she realizes the glove is not in her hand, and rushes back to the place she dropped it, only for it to disappear. And in a split screen shot, Kate realized where it was the whole time: on the man she grew smitten with. She follows the man again, through several twists and turns throughout the museum, trying to catch up. She tries to move faster and faster, only to lose the glove and the man, losing her one last chance at excitement. She leaves the museum thereafter, but soon finds the white glove hanging out of a taxi. At last! She can finally be whole again. And with the man opening the cab door, the two finally start to talk, and passionately kiss while in the cab, as they drive back to the man’s apartment.

Everything about this moment is brilliant, solely through the art of voyeurism. In cinema, voyeurism allows viewers to see the world from another character’s point of view. The world they inhabit, the people around them, their inner emotions. It’s in this moment we know who Kate Miller is and what she wants out of life. She wants a man who excites her, who enthralls her. Somebody who understands her. And we get to see the struggles she has at home as a bored housewife. This 10-minute sequence is done with almost no dialogue, and is solely conveyed through visuals, music, and fast editing. It’s the perfect example on how film language can make a viewer understand someone’s viewpoint without a single piece of expositional dialogue.

With all that said, while De Palma is known for his incredible film language, this film is far from perfect, especially when it comes to its treatment on its transgender antagonist. As said before, the killer is a transgender woman named Bobbi, but what the film reveals at the climax is Bobbi is Robert Elliott. According to a psychiatrist at the end of the movie, Elliott was at a battle between their female and male side. Elliott wanted to be a woman, but their male side forced him away from sex reassignment surgery. And through their mental confusion, this results in the creation of Bobbi, their murderous female side that comes out whenever a woman sexually arouses them. This is because such arousal was considered a thread to Elliott’s female side, causing a murderous tendency to jump out.

It’s very clear the problem with such a character comes into play. Essentially, Robert Elliott is confused and terrified of changing gender, which causes mental deterioration and results in the murder of other women. It plays into a slew of harmful transgender stereotypes that make the film uncomfortable and potentially dangerous. And while it is important to understand that 1980 was a very different time, it is still very important to call out and acknowledge these harmful depictions. Media internalizes certain messages, and it’s important to critique these messages to improve situations for those who are discriminated against.

But even with such harmful messaging, though it is understandable people may not be able to look past that, the film is still very, very strong. De Palma’s direction is sleek and stylish, the performances consistently deliver, and the mystery is clever and gripping, resulting in a sharp homage to Hitchcock’s work. The film would go on to see great reviews from critics, in spite of three Golden Raspberry nominations with David Denby of New York Magazine citing the film as “the first great American film of the ‘80s”.

And alongside strong box office, netting $31.5 million, this only helped further De Palma’s unique film career that would last throughout the rest of the 1980s and beyond. And while Philadelphia was really only featured in one sequence, though perhaps the most crucial of them all, De Palma’s next project would be all about this glorious city.